The Jewish Window of Amsterdam (street name has been distorted intentionally)

As I wrote this I realized this story is filled with so many of the attributes I believe exist in so much of today’s world, be it Jewish or not. The 2 most prevalent in what you are about to read are on 2 different sides of the emotional spectrum. The first one is sadness, the second one is hope. Spoiler alert and good news for those who prefer to feel optimism and inspiration from what they read. I conclude with hope.

It should be noted as I start this piece that in my recent trip to Holland I spent all but one day in Amsterdam and only prayed in one synagogue, a warm and welcoming one in the Amsterdam suburb of Amstelveen. So although I believe in the information I am sharing, I acknowledge that it is indeed based mostly on my opinion and on a relatively small sample of experience. That being said, my feelings are feelings I feel strongly about and are also based on the truth of what Dutch Judaism once was.

It is also important that I mention that in all my interactions with anyone Jewish during my 6 days in Holland I found people to be friendly and agreeable. Also, although I have heard a lot about European anti-Semitism and do not question the accuracy of the reports, I personally was exposed to no specific evidence of it during my trip. So although it is possible that infighting is still a thing in Dutch Jewry and it is certainly possible or even likely that anti-Semitism is on the rise in Holland as it is in so many parts of Europe, it would be disingenuous on my part to claim a negative experience where one doesn’t exist.

So then from a Jewish standpoint, what was it that pained me most about my recent trip to Holland? It had to do with how little of Dutch Jewry was left and my perception of what so much of Judaism in Holland has become. It’s become a tourist attraction.

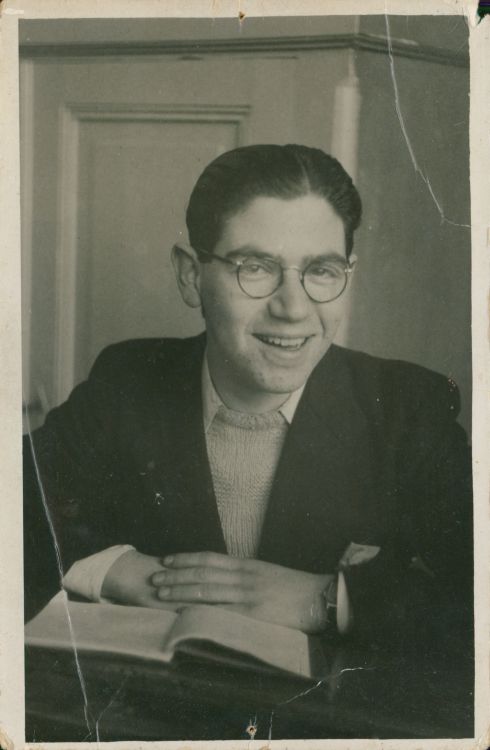

Part of this is no surprise to anyone reading this piece. After all, ask anyone about what they know about Amsterdam and they will undoubtedly mention Anne Frank’s house, the Portuguese Synagogue, or both. Two places that hold different meaning to me than they do to so many others, be they Jewish or not. Although I appreciate the attention Anne Frank’s house brings to the history of the Jews in Holland and Europe, and I believe in anything that teaches the world the horrors of Nazi-occupation, having had a mother who hid during those years and survived to tell her story, Anne Frank’s house is not so much for people like me as it is for people with no personal connection to the history.

The Portuguese Synagogue, a thing of beauty, was the synagogue my mother belonged to as a child. In my recent visit to the place Dutch refer to as the “Esnoga”, more than half of my time was spent looking through the records to find membership cards of people I descend from. When I walked into the main sanctuary I felt a connection, knowing that many years back there were many people related to me that called this place home, regardless of how regularly they attended. As beautiful of a place as it is, and as many pictures as I took, it was so much more to me than a mere tourist attraction.

The day after the event in which Wim de Haan gave the violin his father protected for my Uncle Bram to me and my siblings, I went on my own private tour of Amsterdam. On the canal ride we passed what the tour operator referred to as the old Jewish section. When I went back to what was previously the Dutch Jewish Hospital (NIZ) and the Jewish Invalid Hospital (The Joodse Invalide), despite the powerful connections I felt, these institutions were brought down to very little more than a few plaques.

On the way back to the immediate area near the Portuguese Synagogue I found a bank of a canal that had a memorial of 200 residents of the immediate area. The memorial was known as the “Shadow Wall”, plaques put into the ground near the banks of the canal.

When I stood in front of the Esnoga, to the left was an entrance to a side street with a banner that read “the Jewish Quarter” where a Jewish Museum now stands. If you cross to the right you find yourself on the Rappenburgerstraat, the street my father spoke of often and always represented the heart of my father’s Jewish life and the center of so much of Amsterdam’s Orthodox Ashkenazi Jewish world. I walked up and down the street, a street once filled with synagogues and Jewish schools, only to find another plaque and some buildings with some Hebrew writing.

In conversations I had with non-Jews while in Holland, I found them to be gracious, kind and compassionate about what once was while also in many instances detached as anyone would be towards something so far removed from their reality. In my contact with Jewish people during my trip, as I indicated earlier I found them to be warm and pleasant, including my time praying in the synagogue in Amstelveen. In my contact with both parties I came to the conclusion that neither the Jewish people in Amsterdam nor the non-Jewish Dutch citizens of Holland are responsible for what Dutch Jewry has become. That being said, the reality as I saw it was that it is now more a tourist attraction than it is a thriving community. As I walked through parts of a city that sometimes felt to me like a Jewish graveyard, a city at the very core of my roots, I felt an immense sadness.

But then I saw the window. Having concluded the final part of my tour of Jewish Amsterdam I began to walk towards Amsterdam’s Central Station. Walking past the market, numerous shops, bars and restaurants, I came to a corner with a souvenir store, where in the window above this little store I saw the most organic symbol of Judaism I had seen not only in all of Amsterdam, but anywhere in a long time. The symbol I would come to see as the faint heartbeat of what once was a city in which 1 in every 10 people were Jews. In that window I saw a Menorah, 2 Sabbath candle holders, and a spice box used for the Havdalah ceremony on the conclusion of the Sabbath. Although not something anyone would pay to see, for me personally it was one of the most fascinating images of my entire trip.

The fact that my perception of Judaism in Holland had dwindled down to not much more than a tourist attraction is not meant as an indictment of Dutch Jews or non-Jews, rather another reminder of the evil precision in which Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party destroyed a civilization in Europe. That being said, that one small window in the center of Amsterdam felt to me like a flame that was never extinguished and a the hope that Judaism might one day thrive again in Amsterdam.

LIKE THIS POST? SHARE IT ON FACEBOOK OR TWITTER

READ MORE OF WHAT I HAVE TO SAY IN THE COMMON SENSE LIBERAL

JOIN “THE GLOBAL COALITION FOR ISRAEL” ON FACEBOOK

GLOBAL COALITION FOR ISRAEL IS NOW ON TWITTER @gcimovement

IN CONJUNCTION WITH GLOBAL COALITION FOR ISRAEL